By a Former FUTA Comrade

Introduction

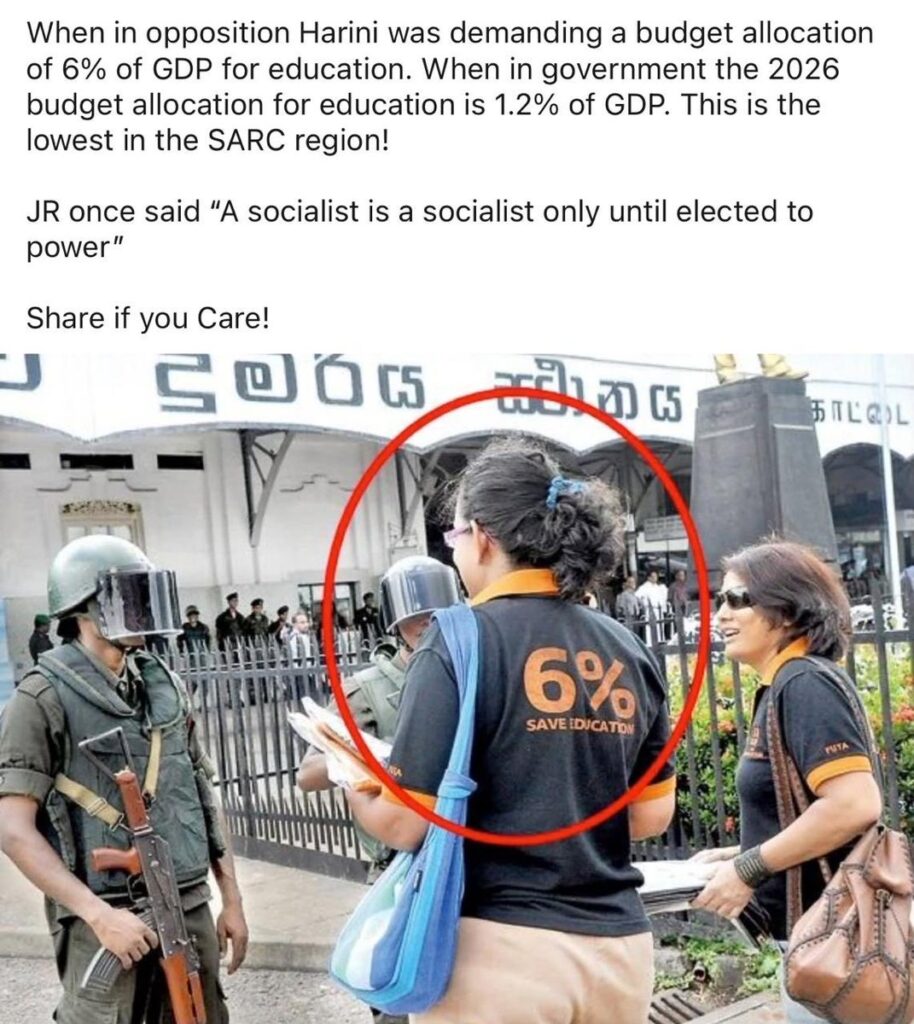

This article, written by an anonymous senior academic and former FUTA activist, offers a scathing critique of Prime Minister Harini Amarasuriya. It highlights the perceived hypocrisy between her past activism—which demanded an immediate 6% GDP allocation for education—and her current refusal to implement it. The author accuses the Prime Minister of political opportunism, historical revisionism, and betraying the academic community that once rallied behind her.

Summary

The author expresses a deep sense of professional betrayal, contrasting Dr. Amarasuriya’s past role as a fierce advocate for an immediate 6% GDP allocation with her current stance, where she claims such a promise was never made to be fulfilled immediately. The piece argues that the Prime Minister is engaging in "gaslighting" by trying to rewrite the history of the FUTA struggle, which explicitly demanded immediate funding rather than gradual structural reform.

The writer posits a damaging dilemma regarding the Prime Minister's competence: either she was previously ignorant of the university system's inability to absorb funds (making her past advocacy reckless), or she cynically used an unachievable demand solely to build her political career. The article condemns her for now adopting the very arguments (fiscal constraints and lack of capacity) that she once ridiculed previous governments for using. Ultimately, the author asserts that her failure to produce a viable implementation plan after 13 years proves that the movement was used as political theater, severely damaging her credibility and trust as a national leader.

I marched beside Harini Amarasuriya to Colombo, we chanted in unison, our voices hoarse with conviction: “Six percent for education, not tomorrow, but today!” The scorching sun beat down on our backs as we carried banners demanding what we believed was a non-negotiable baseline for a functioning public university system.

Dr. Amarasuriya was our intellectual north star, articulating with pedagogical precision why anything less than 6% of GDP was an existential threat to higher education in Sri Lanka.

Today, as Prime Minister Amarasuriya stands in Parliament rejecting the immediate allocation of that same 6%—claiming “no such promise was made”, I write not as a political opponent, but as someone who feels the sting of professional betrayal.

I speak for the academics who sacrificed salary increments, who faced water cannons, who endured public ridicule as we fought what we believed was a righteous battle for educational equity.

We deserve an explanation that goes beyond political expediency.

What we have witnessed is not pragmatic adjustment to fiscal realities. It is something far more troubling: a combination of historical revisionism and a revelation of fundamental incompetence that should concern every Sri Lankan, regardless of political affiliation.

Prime Minister Amarasuriya’s recent statement that her government never promised an immediate 6% allocation is not merely a political pivot, it is a systematic attempt to rewrite the pedagogical history of this nation. As education professionals, we understand the importance of accurate historiography. The FUTA campaign from 2011 to 2015 was unambiguous in its demands.

We did not march for “gradual structural reform leading eventually to improved funding mechanisms.” We demanded immediate budgetary reallocation to prevent what we diagnosed as the imminent collapse of public higher education.

The documentary evidence is incontrovertible. Our memoranda to the Treasury, our public statements, our negotiation demands, all called for immediate implementation. When then-Minister Rajitha Senaratne argued in 2012 that the system lacked the absorptive capacity for such a dramatic increase, we rejected his position as capitulation to neoliberal austerity.

Dr. Amarasuriya herself authored position papers arguing that administrative capacity concerns were smokescreens used by an uncaring government to justify educational neglect.

Now, occupying the very seat of power we once protested against, she deploys the identical arguments. The cognitive dissonance is stunning. If her current position, that we need phased implementation alongside structural reforms—was always the correct approach, then our entire struggle was built on flawed premises.

If it was not always her position, then she is engaged in what educators call “motivated forgetting,” selectively erasing inconvenient truths to maintain political viability.

This is not nuance. This is gaslighting an entire generation of academics who believed we were fighting for educational transformation, not serving as stepping stones for political careers.

As education professionals, we teach our students that effective advocacy requires more than passionate rhetoric—it demands comprehensive implementation frameworks. The most damaging revelation in Prime Minister Amarasuriya’s recent statements is not her policy reversal, but her implicit admission that she never developed a workable plan to achieve the goal she championed for years.

Her current argument—that we cannot simply allocate 6% without first reforming administrative structures, improving absorptive capacity, and addressing systemic inefficiencies—raises a devastating question: Why was this implementation roadmap absent during the years of protest?

The pedagogical implications of this gap are severe. We face two equally troubling possibilities:

Scenario One: Ignorant Advocacy.

Dr. Amarasuriya did not understand in 2012 that the university system lacked the infrastructure to effectively utilize a dramatic funding increase. This means she led a national campaign that disrupted thousands of students’ education, paralyzed the university system, and contributed to political instability—all while fundamentally misunderstanding the technical requirements of her own demand. As an educator, she would have failed her own students for submitting such an under-researched proposal.

Scenario Two: Cynical Mobilization.

She understood the implementation challenges but chose to demand 6% anyway, knowing it was unachievable without reforms she had no plan to execute. This transforms the FUTA campaign from legitimate advocacy into political theater—street protest as curriculum vitae building rather than genuine educational reform.

Neither scenario reflects the competence we expect from someone now managing national policy. In academia, we hold our graduate students to higher standards of intellectual rigor. A doctoral candidate who identified a problem but offered no viable solution methodology would not pass their defense. Yet we are asked to accept this from our Prime Minister on her signature policy issue.

The 2011-2012 period was marked by significant disruption. University calendars were suspended. Students lost academic years. Public trust in higher education eroded as institutions became symbols of political contention rather than centers of learning. The social cost was measurable in delayed graduations, interrupted research programs, and deteriorating infrastructure as maintenance budgets were sacrificed during the crisis.

If Prime Minister Amarasuriya’s current position is correct—that the path forward requires gradual increases synchronized with administrative reforms—then the radical tactics deployed during FUTA’s campaign were not merely excessive but counterproductive. We did not need street protests that shut down the education system; we needed technical working groups developing implementation frameworks. We did not need confrontation with the Treasury; we needed collaboration with educational planners to build absorptive capacity.

The irony cuts deeper when we consider the JVP’s role. The party provided organizational infrastructure, political cover, and mobilization capacity that transformed FUTA from an academic union into a national movement. JVP activists risked arrest, injury, and surveillance to support what they believed was a struggle for educational justice.

They invested political capital in a demand that their now-Prime Minister admits was impractical without reforms that were never articulated.

This represents a profound betrayal of comrades who acted in good faith. The JVP machinery was used to build individual political profiles through a campaign that, we now learn, lacked the technical foundation for implementation. Those who sacrificed for this struggle deserve better than retrospective justifications that invalidate their efforts.

Let us examine the current budgetary reality with the analytical rigor we demand from our students. The allocation stands at approximately 2.04% of GDP—effectively unchanged from the levels we deemed catastrophically insufficient during our protests. The supplementary allocation of Rs. 7.04 billion, while not trivial, represents a marginal adjustment rather than the transformative reallocation we fought for.

Prime Minister Amarasuriya now faces precisely the constraints that previous governments cited to resist our demands: competing budgetary priorities, debt service obligations, limited fiscal space, and questions about institutional capacity. When Ministers under previous administrations made these arguments, we dismissed them as evidence of misplaced priorities and lack of political will. We organized protests. We gave media interviews questioning their commitment to education. We wrote op-eds attacking their “neoliberal” values.

Now our former comrade offers identical justifications from the opposite side of the negotiating table. The constraints, apparently, were real all along.

If previous governments were “enemies of education” for failing to allocate 6% under these conditions, then by the same standard, Prime Minister Amarasuriya has joined their ranks. If these constraints justify her current approach, then we owe apologies to the Ministers we vilified for wrestling with the same budgetary realities. The consistency we demand in our students’ academic arguments must apply to our political positions as well.

The combination before us is particularly troubling for those of us who value both educational policy expertise and governmental integrity. Prime Minister Amarasuriya’s trajectory reveals two intersecting failures.

First, there is demonstrated incapacity to translate advocacy into implementation. After thirteen years, there remains no comprehensive reform proposal—no detailed roadmap showing how to build administrative capacity, no timeline for phased increases tied to institutional readiness, no metrics for evaluating successful absorption of additional funding. For someone whose academic career and political rise were built on this single issue, the absence of such documentation is inexplicable. We teach our undergraduates to develop more thorough capstone projects.

Second, there is the attempted revision of historical record. Rather than acknowledge the evolution of her thinking or admit that the original campaign lacked implementation sophistication, she denies that immediate implementation was ever the demand. This insults the intelligence of everyone who participated in those struggles. We were there. We heard the speeches. We read the position papers. We know what we demanded and why.

The epistemological crisis this creates extends beyond education policy. If a leader will rewrite the history of her signature issue—the domain where she presumably possesses greatest expertise—what confidence can we have in her representations on matters where her knowledge is less developed? Economic policy? Foreign relations? National security?

Trust, once broken, permeates every interaction. A Prime Minister who cannot maintain intellectual honesty about her own professional background creates systemic uncertainty across all policy domains.

As educators, we know that the most valuable learning often comes from failure—but only if we honestly confront our mistakes rather than rationalize them away. The FUTA campaign’s failure to achieve its stated goals despite years of disruption should prompt genuine institutional reflection. What did we misunderstand about educational policy implementation? How can future advocacy be more technically grounded? What damage was done to the university system by tactics that prioritized visibility over viability?

Prime Minister Amarasuriya had an opportunity to model intellectual growth: to acknowledge that youthful idealism, while admirable, had given way to a more nuanced understanding of implementation complexity. Such honesty would have been pedagogically powerful, demonstrating that leadership involves learning from experience and adjusting positions based on new information.

Instead, we received historical revisionism and hollow promises that “structural reforms” are underway without any transparency about what those reforms entail, who is designing them, or when they will enable the funding increases we were told were non-negotiable.

In my years teaching educational policy, I have evaluated countless student proposals for systemic reform. I apply consistent criteria: problem identification, causal analysis, solution design, implementation planning, and resource allocation. A proposal that identifies a real problem but offers no viable implementation pathway receives, at best, a failing grade—and that’s from a student, not from a Prime Minister who built her career on this exact issue.

The current allocation of approximately 2% of GDP, supplemented by modest increases that fall far short of transformative change, represents an admission of defeat. It confirms that the 6% demand, as articulated during our years of protest, was not a carefully calibrated policy position but an aspirational slogan disconnected from implementation realities.

Sri Lanka does not need leaders who master the art of opposition rhetoric only to discover upon assuming power that governance is more complex than they anticipated. We need leaders who understand implementation challenges before mobilizing national movements, who develop comprehensive reform frameworks before shutting down university systems, who speak honestly about past positions before asking us to trust their future promises.

I marched for educational justice in 2012 because I believed we were part of a carefully considered campaign for transformative change. Today, I write with the heavy knowledge that we may have been participants in political theater—extras in someone else’s journey from activist to administrator.

The pedagogy of betrayal teaches us that the loudest voices in opposition are not always the most competent voices in governance. It teaches us that disruption without implementation planning is activism without responsibility. Most painfully, it teaches us that the comrades who march beside us today may deny we ever marched together once they reach their destination.

Dr. Amarasuriya has taught us one final lesson, though not the one she intended: it is far easier to demand the impossible than to deliver the achievable. Sri Lanka deserves leaders who understand this before taking office, not after.

The Emperor has no clothes, and those of us who helped weave the illusion bear our share of responsibility. But unlike our former comrade, I will not pretend the fabric was there all along.

The author is a senior academic who participated in the FUTA campaigns and wishes to remain anonymous to protect against professional repercussions while speaking truth about a movement that has lost its way.